“He can’t be reversing on the motorway.”

He – the bus driver – had missed the exit, shortly before the Serbian border. The bus was now parked on a Croatian motorway, cars zipping by in the faster lanes. There was no hard shoulder. The bus conductor peered out the window and muttered something indecipherable to the driver, who nodded. There was a collective tightening of seatbelts as the driver reversed 100 yards, then steered up and onto the slip road he had missed. The journey continued with a sigh of relief, and half an hour later the bus arrived in Serbia.

Belgrade, Serbia’s capital, is much larger than Ljubljana, the previous stop of this journey. Built around the confluence of the Sava and the mighty Danube River, it houses more than one million inhabitants and was the capital of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, SFRJ – or Yugoslavia, for short.

A sprawling fortress stands on a hill at the centre of the town, the site of 140 battles. It has reportedly been destroyed and rebuilt over 40 times since being founded by the Romans. Romans, Slavs, Franks, Bulgarians, Hungarians, Serbians, Ottomans, Austrians, Nazis, Communists – a multitude of different peoples and regimes have lain claim to the fortress’ walls over the centuries. But it is in the bustling, modern town below that the most intriguing recent history has played out.

Losing one’s life savings is a scenario no-one likes to contemplate. But in the chaos of the post-Communist days in the 1990s, with wars raging in the newly independent republics, this scenario beset millions of ordinary people in ‘rump Yugoslavia’ (Serbia, including Kosovo, and Montenegro, which had chosen to remain in the union).

The transition from communism to capitalism is not a smooth road – ask anyone in Russia in the 1990s. Into this already challenging scenario mix in significant government mismanagement of the economy, add a generous dose of Western sanctions in punishment for Serbian atrocities in the Balkan conflicts, and sprinkle on top the strain that fighting various wars will have. These ingredients are a recipe perfect for hyperinflation.

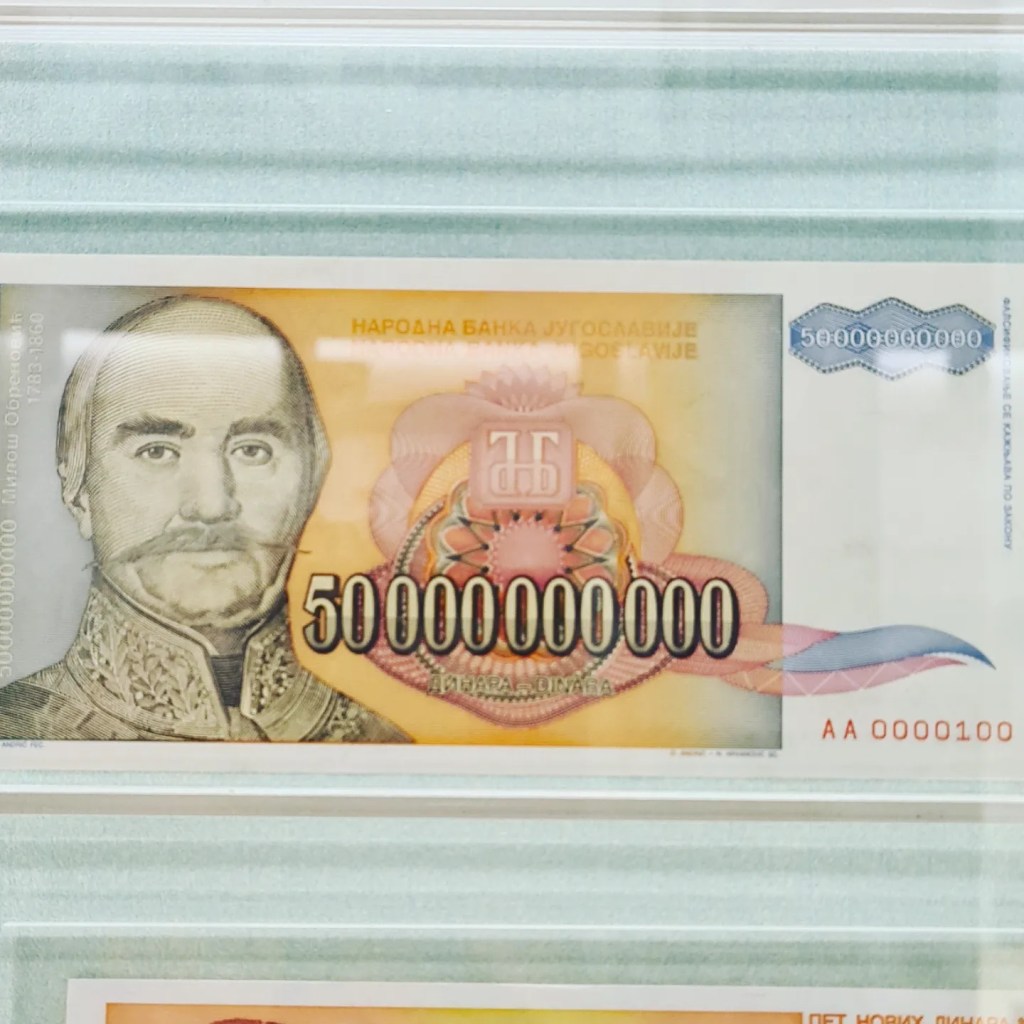

Today, the National Museum of Serbia displays a bank note for 50 000 000 000 (50 billion) dinar. The adjacent information panel reports that it lost nine tenths of its value after one week. For almost two years, from 1992 to 1994, what is now Serbia experienced some of the worst hyperinflation in modern history, peaking at a monthly rate of 313 million percent. People struggled to pay their bills, or to put food on the table. Organised crime flourished. Yet even in these hard times, Serbians maintained a sense of humour and cynicism. A local explained that there was a long strip in the city centre where every bar and club was owned by gangsters. Belgradians nicknamed the road ‘Silicon Valley’, due to the mafiosos’ propensity for always being accompanied by glamorous girlfriends sporting various surgical, silicone enhancements.

Fortunately, in 2022, this is now in the past. Yugoslavia anchored its currency to the German Mark and brought inflation under control. Belgrade today is buzzing with life. Whilst Ljubljana was awash with retailers of outdoors and adventure gear, Belgrade is peppered with bookshops. Bookshops serving coffee to customers, bookshops open past 9pm, even a bookshop that doubled as a cat café. A student was proud to tell of how their degree was free, in contrast to some Western countries.

Belgrade is also renowned for its nightlife; its clubbing scene was recommended by at least four different people before this trip. Walking around, there is a vast array of restaurants and bars. Craft beer is in vogue. And live music, often of the traditional variety, featuring accordions, is widespread. A young Welshman said on Monday that the previous night, Sunday, he had partied until 4am in one of the city’s famous floating nightclubs, on a boat moored on the banks of the Sava, with a live band providing all the music. There are few nightclubs in the UK playing live music until 4am, fewer still that can claim a river boat setting.

That is not to say that Serbia has got everything right. Homophobic graffiti is daubed on walls, and the country recently stirred up controversy by banning a ‘Europride’ march its capital, despite its female Prime Minister being openly gay. A tour guide appeared largely progressive, and referred to Serbians being “brainwashed” by former President Slobadan Milosevic; Milosevic died in 2006 whilst on trial in The Hague, facing 66 counts of crimes against humanity, genocide, and war crimes. But the tour guide still referred to the Balkans conflicts as “civil wars”, i.e. inferring that the bloody conflicts in Bosnia and Croatia were solely confined to combatants of those countries and that the state of Serbia was in no way involved. Most historians would refer to these as international wars, acknowledging the (often shameful) role Serbia played. It appears that Serbia is still coming to terms with its recent past. In 2013 their president offered an apology for the Srebrenica massacre, in which Serbian forces massacred 8000 Bosnians, but declined to call it genocide.

These issues aside, it was an enjoyable trip. An unexpected highlight was dinner in a restaurant that turned out to be a shrine to Josep Broz Tito, the Yugoslav Communist leader from 1945 until his death in 1980. Posters of Tito, and assorted memorabilia, adorned the walls. Dozens of books concerning Tito filled the shelves. There was even a photo of Tito affixed to the ceiling. For a neutral observer who is simply interested in history, this was a fascinating place to have a meal.

It would seem that, whilst Belgrade generally wants to move on from the dark times of the 1990s, in some quarters at least it still idolises the halcyon days of the SFRJ in the 1970s and before. What the next stop should reveal, in Sarajevo, Bosnia, is whether people in the other ex-Yugoslav countries remember Tito in quite the same way.

Leave a comment