There are few places on earth that remain untouched by the technological advances of the last 150 years. Bichhya, a remote village in northern Nepal that lacks roads, plumbing, internet or mains electricity, is one of them.

As part of a round-the-world trip I wanted to spend some time volunteering in a medical capacity. Despite being a fully qualified doctor, this proved more difficult than anticipated to organise. Most medical charities nowadays feel that, to be of genuine help rather than a hindrance, you need to commit at least three to six months to working with them. I required a briefer placement.

The charity PHASE (Practical Help Achieving Self-Empowerment), set up by a group of Rotherham GPs in 2005, proved the perfect fit. PHASE employs over 150 workers in Nepal, operating in healthcare, education, research and reconstruction after the 2015 earthquake.

One of PHASE’s main projects is to train and fund healthcare workers to practise in very rural communities that otherwise have no access to healthcare. Such staff, known as Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (AMNs), have only 18 months’ training, and must then function independently, essentially as a rural GP, nurse and midwife. In contrast, a GP in the United Kingdom would have at least five years of medical school training and five further years of on-the-job supervision as a junior doctor before practising independently.

The AMNs do a fantastic job living in and serving their rural communities. However, due to their limited training, they are grateful for additional teaching. Therefore, PHASE also facilitates visits from British GPs, who live with the AMNs for a week or so and provide supervision and medical tutorials for that period. It was in this capacity that I journeyed to Bichhya, northern Nepal.

Bichhya is a village of around a hundred inhabitants, nestled on a Himalayan mountainside between 1500m and 2000m above sea level. The closest road is an eleven-mile hike along physically challenging, rocky paths that in some areas have been obliterated by landslides; there is no vehicular access. The journey from Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu, takes three days: two internal flights on the first day, a day in a local jeep, squeezed four-to-the-back-seat and bumping so much that sometimes your head hits the roof on the second day, and the aforementioned hike on the third day. The journey is simultaneously breath-taking – fantastic mountain vistas, especially from the window of the second internal flight, a nineteen seat propeller plane that flies in between, rather than above, the valleys – and slightly frightening.

Stone and timber houses flanking narrow dirt streets greet you on your arrival. There is no running water in the residences: the only water comes from a couple of communal taps that are fed by pipes connected to streams further up the mountainside. There is no central heating, only fires, and certainly no internet. Three shops sell basic goods, mainly soap and pot noodles; anything beyond this would need to be transported in by mule train and is largely unavailable.

There are only three clues in the village that this is the 20th or 21st century, as opposed to the 15th:

- Some electricity, from solar panels on the roof of buildings. This powers light bulbs and mobile phone charging (there is limited telephone reception for calls and texts) until the solar-charged battery runs out for the day. Then you must wait for the sun to come out again.

- Communal squat toilets, which are muddy and unpleasant, but better than nothing.

- An unfortunate proliferation of plastic waste. Bichhya is too remote for organised refuse collection and waste has to be burned, but often is not.

I was greeted by three PHASE AMNs, plus a more senior PHASE health supervisor who was visiting Bichhya for three weeks. The AMNs live in Bichhya permanently, in the office, a five-minute walk from the health post. Two had very good English and could translate for the rest of us.

An emergency can turn up at any time of day or night. Otherwise, the AMNs open the health post six days out of seven (Nepalis work a six day week); Saturday is the day off. I observed them seeing the patients that turned up each day.

Before arriving I had felt some trepidation. What if my training in the UK had not prepared me for the exotic conditions I might encounter out here? These fears proved unfounded. The most common reason for attendance was a cough, similar to GP patients in London. The caveat was that a greater proportion of those turning up had deep-seated chest infections, as opposed to mild viruses, and I suspect a number who were coughing up blood and getting sweaty at night had tuberculosis.

The second most common condition was gastritis/indigestion. Nepalis eat two large meals per day, one just before bedtime. The meals are often spicy. Many then develop indigestion and acid reflux.

Some more challenging cases also presented. One was a teenage girl who had been married at the age of thirteen – illegal in Nepal, and we took all the safeguarding steps that were available to us in this setting. I can only hope that this is followed up.

Another case was a woman whose previous pregnancy had ended with obstructed labour, i.e. the baby got stuck whilst being born. The Nepali government funds emergency helicopter evacuation for women in remote areas that experience complications in labour, but unfortunately despite this she lost the baby. She was now pregnant again, 35 weeks, and determined not to go to hospital. After extensive discussions her family offered to club together and pay, and she agreed to journey to the nearest obstetric unit for the next birth. Interestingly, obstetric emergencies are the only emergency that the government funds emergency evacuation for. Anything else – from heart attack to meningitis to major trauma – and the patient will need to make their own way to the hospital.

One day per week the Bichhya PHASE team undertakes an ‘outreach clinic’. This means trekking a couple of hours along the valley to an even more remote village, Bama, and holding a clinic there for the day. This was the most scenic commute I have ever experienced. The AMNs were keen to point out a spot on the mountain path, about a mile and a half from either village, where they recently delivered a baby.

Another day was the quarterly meeting of local Female Health Volunteers. These are women with no medical training, who visit the Bichhya health post every three months to receive teaching on how to safely deliver a baby. Many had walked for three or four hours to attend. Topics covered included handwashing, prevention of hypothermia in the new-born, recognising signs of infection, breast feeding, and new-born resuscitation.

One day, a middle-aged woman arrived at the health post saying that she was concerned that her elderly father, who was too unwell to travel, was very ill with a chest infection. We agreed to a home visit. The AMNs told me that he lived “in the village”, so we set off at the end of the day to visit him. Halfway up the mountainside, with the sun setting, I clarified the address: in fact, the patient lived a good hour’s hike up the mountain from the village. It would be dark by the time we arrived, and pitch black for the return journey.

It remains unclear whether the team were not concerned about climbing the mountain in the dark, or whether they were proceeding out of deference to the visiting doctor. Either way, we all agreed that it would be unsafe to continue. I was troubled by leaving an unwell patient without attention, but I could not endanger the healthcare team with a rash mountain hike after sunset, so we went home and returned the following day.

Upon arrival, after a vertigo-inducing trek up some very exposed mountainside paths, the elderly man was completely well! This was another similarity to the UK: sometimes, a home visit is requested when it is not required. I was impressed to learn that the man’s granddaughters, who lived with him, made the same journey I had just made every day for school. This would be a round trip of over two hours, up and down the mountain.

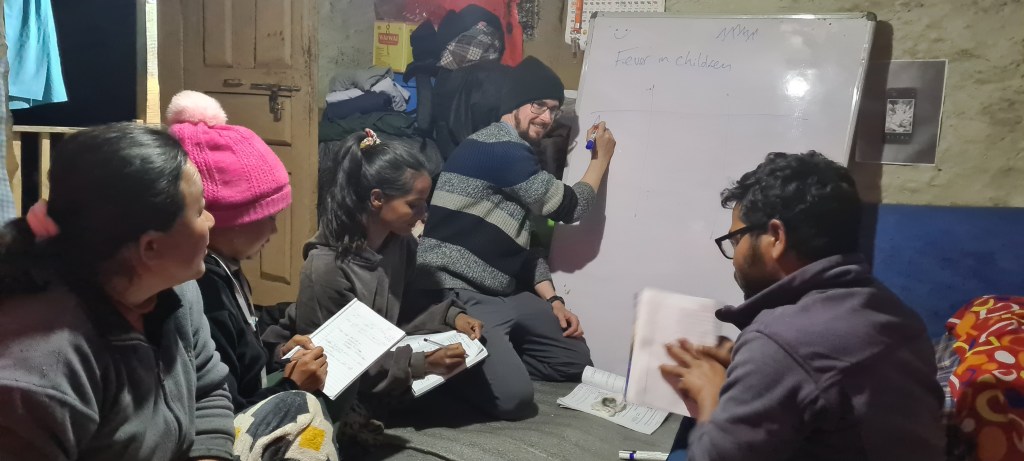

The AMNs were very grateful to have me around and kept me busy by requesting tutorials right up until 9pm every day. The respiratory system, the gastrointestinal system, neurology, gynaecology, rheumatology, paediatrics, medical emergencies…we covered the body head to toe, and then some. Tutorials in the afternoon were held outside the health post with the valley stretching out before us.

The food was locally cooked (most villagers are subsistence farmers), healthy and filling, albeit mostly the same: rice and lentils for breakfast, rice and lentils for dinner, every day. Portions are very large, and the Nepali approach to seconds is similar to the fictional Mrs Doyle serving tea in Father Ted; “Go on, go on, go on.” Second, third and fourth helpings are constantly offered, and it feels rude to refuse. Coupled with the AMN’s well-intentioned hospitality, always insisting that I take the seat closest to the fire, this resulted in a few uncomfortable mealtimes, feeling stuffed full of rice and sweating a foot or two away from the open flames. Eventually, I had to start refusing seconds and asking for smaller portions. These requests were usually not adhered to, such is Nepali hospitality.

Living amongst the healthcare team in such a rural setting was an eye-opening experience. Their commitment to learning was remarkable. In one instance, one of the AMNs was thrilled to receive a book via the mule train that she had previously ordered. I presumed it would be fiction, a novel to keep her occupied during the quiet times in the absence of television or internet. But it was a nursing textbook, which she excitedly showed to me and announced she would study immediately.

It was also impressive to witness the lengths that everyone went to in order to maintain excellent levels of hygiene despite the challenging conditions. A huge amount of time was spent filling buckets with water, washing kitchen utensils and washing bodies. A large chunk of our day off, Saturday, was spent hand-washing clothes with soap and water at the village tap.

It was a privilege to share their lives for a short while. I learned a lot and came away re-enthused for general practice in my normal setting in the UK. It appeared that the AMNs learned a lot too, and they seemed very grateful for all the teaching. Hopefully I’ve made a small difference.

If any UK doctors are interested in volunteering abroad, but are constrained to an annual leave-type time frame of a fortnight, then teaching, rather than practising, medicine for that period may be the best way to go. Consider a placement with PHASE and feel free to contact me via the comments if you have any questions.

phaseworldwide.org/

Leave a reply to Bridget Bradley Cancel reply